And the truth is, there is nothing ordinary about life. There is nothing ordinary about anyone’s life.

Some historians and certainly ‘big historians’ seem to be captivated by the knowable: the concrete facts (and enduring buildings and structures) that attest to the past. As I try to figure out why history now intrigues and engages me, I come to realize it’s the unknowable, the stories between and around the few facts that have survived. It’s about the mystery we uncover and the imagination we must marshal as we explore the past.

Why would I say history is unknowable? Think about it. Think about the lasting traces you are leaving of your own everyday life just this one day or this week. Not much, eh? (At least not in the pre-blogging era.)

So how much can we know about the lives of people more than a hundred years ago? We find small hints and try to put the pieces together. We talk to people and hear the stories that have come down, second-hand, third-hand, more. We puzzle together the lives and events of the past, and use our intuition, our sense of empathy, and our imaginations to do it. We project ourselves into the past. As we explore what these people were about, we learn a little more of what we are about.

I think maybe we want to understand the meaning of their lives because we want to understand our own lives.

Each answer leads to another question; that particular answer asks “when do lives have meaning?” That’s a BIG one. Or, taken from a different angle, “what can we learn from the lives of people who used to live here?” That’s a little easier to chew on.

For me, the key word is “here,” because history is the intersection of people and places. Who lived here? Why did they live here? How did they survive here? What did they do here?

That’s why I do what I do, why I’m developing this passion for history. It’s all about place. You see, my original passion is ecology and natural history, the story of places. When you add people to that mix, you get history. Eureka!

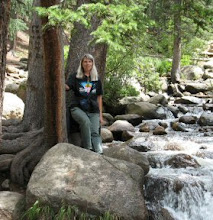

Here’s a picture of "the place," taken this morning as the rising sun hit the rocks.

Visit Red Rocks for more info on this place.